Peter Greenaway

I turned 18 the year that Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover was released, I saw its opening at the Lumiere Cinema in London and it blew me away. Around the same time Channel 4 screened his previous films, which they also co-produced via their Film Four funding arm, The Draughtsman’s Contract, A Zed & Two Noughts, Belly Of An Architect and Drowning By Numbers. Each featuring memorable Michael Nyman scores and striking, exquisitely lit, photography by veteran nouvelle vague cinematographer, Sacha Vierny; who notably shot Alan Resnais seminal, 1961 work, L’Année Dernière à Marienbad. At the time of its release Greenaway was studying at the Walthamstow College of Art, specialising in murals.

After graduating in 1965 he took a job at the Central Office Of Information making short documentaries on various banal subjects, such as Trees or Trains. This would lead him to make more experimental, personal projects, allowing him to blend fact with fiction, culminating with The Falls in 1980; a 195 minute mock documentary focusing on 92 survivors of a fictitious global catastrophe, known as the “Violent Unknown Event” or VUE, whose names begin with the letters F-A-L-L. The film also featured original music by minimalist composer, Michael Nyman, marking the start of their long collaboration.

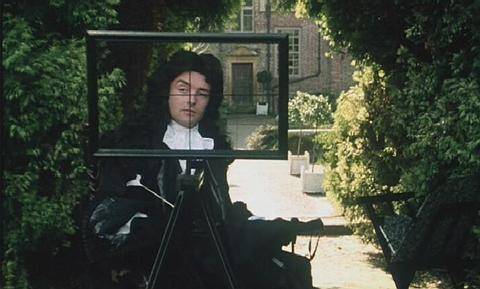

Greenaway’s first totally dramatic feature was 1982’s The Draughtsman’s Contract, financed primarily by Channel 4 which launched the same year. It was the first new terrestrial UK television station for 20 years and its remit was to represent the arts and minority groups. The film is a 17th century whodunit, a young artist is hired to produce a series of landscape drawings of a country estate, the errant owner’s wife agrees to provide the arrogant draughtsman with sexual favours as part of his contract to undertake the work. He also gets physically entwined with the lady of the house’s married daughter until the absent lord of the manor turns up dead in the moat.

The film is packed with visual symmetry, puns and deliberate anachronisms, underscored by Michael Nyman’s scintillating soundtrack, inspired by Henry Purcell, accompanying the 12 landscape sketches. It’s a tightly woven cloth and the film’s success established Greenaway as an original and exciting auteur and his follow up feature was eagerly anticipated.

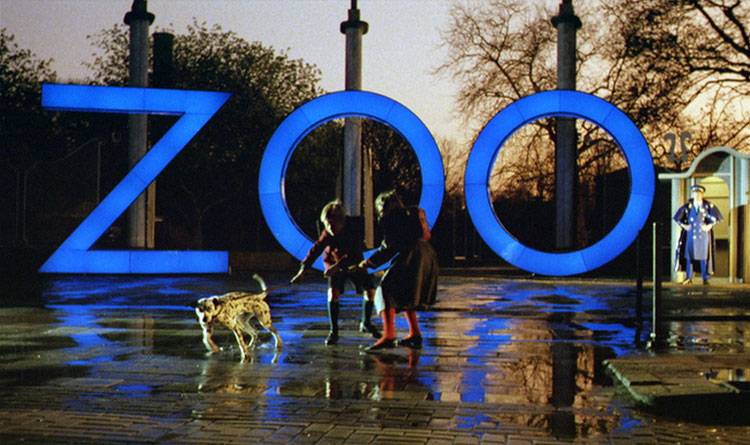

A Zed & Two Noughts, recently released on Blu-ray by the British Film Institute, is an amalgamation of 3 filmic notions; the first is examination of Darwinism, the second a study of the nature of twins and the third is a cinematic history of the use of light as inspired by the Dutch master painter Vermeer and, despite all of this, it manages to be an engaging and amusing black comedy. I shall review the Blu-ray in detail in a future post.

Greenaway’s next film was Belly Of An Architect, starring the American character actor Brian Dennehy. It’s a study of the work of the 18th Century Romanesque architect, Etienne-Louis Boullée. The connection with Rome is further explored as Dennehy becomes obsessed with Caesar Augustus who was poisoned by his wife, Livia. As Dennehy suffers from increasing stomach pains, he suspects his wife is attempting to do the same. I found that this film lacks the charm and humour of Greenaway’s other features and I have never particularly warmed to it.

1988’s Drowning By Numbers could well be my favourite of all of his movies. The combination of humour, intrigue, emotion and game playing is perfectly balanced and you never feel that the style outweighs the substance as I had with his previous film and his work post The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover. 3 generations of women with the same name, Cissie Colpitts, in turn drown their husbands for various reasons, with the help of Madgett, the local coroner, brilliantly played with comic subtlety by Bernard Hill. Throughout the film Greenaway has secretly placed the numbers 1 to 100, serving as both a parlour game for us, the audience, to spot but also signifying our place within the narrative with 50 marking the halfway point, for example.

I particularly enjoy the younger characters, Smut, the Coroner’s son, who counts the surreal, random road-kills that adorn the scenery, and his unrequited paramour, the mysterious ‘Skipping Girl’ who always counts the stars each night. The film has a wonderous, mystical charm and subdued sadness about it, without ever becoming morose; it’s a joy from start to finish (or 1 to 100). The film also contains my favourite Michael Nyman score, taking short phrases from the 2nd Movement of Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, the cues are lyrical and haunting, their mesmeric looping perfectly accompany the film’s obsession with counting.

The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover is Greenaway’s most lavish production and it’s hard to convey this to those who haven’t seen it on the big screen. This film is crying out for a Blu-ray release and I am hoping that the BFI follow this month’s A Zed & Two Noughts fairly swiftly with the rest of his catalogue. The plot, as the title suggests, is concerned with the lives of the characters aforementioned, particularly the cuckolding of Spica, the thief, played with a swaggering vulgarity by Michael Gambon; whose ill-gotten gains allow him to dine at the swankiest of restaurants.

His wife, Georgina, played by Helen Mirren, has been having an affair with nondescript, bookshop owner, Alan Howard, a regular diner who she seduces in the restaurant’s toilets. Once Spica discovers the identity of his wife’s lover he takes his vengeance by having him killed by force-feeding him pages from his books. Georgina discovers the body and has the restaurant’s Chef serve it as a special dish for her husband, forcing him to eat his victim at gun-point before shooting him in the head.

Whilst the plot is fiendishly simple the film’s visuals are sumptuous and stunning, the long tracking shots from left to right, displaying the restaurant’s decor and nouvelle cuisine in primary coloured palettes, took my breath away and will remain as one of the best experiences I have ever had at the cinema. Unfortunately Greenaway’s recent work doesn’t hold a candle to this unbroken run of bold and brilliant movies, however he is just the sort of surprising artist who could yet pull his biggest and brightest rabbit out of his surrealist cocked hat!