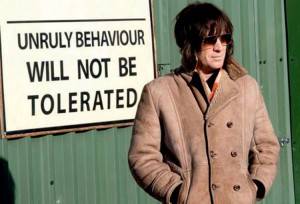

The rights to make a film of Mr. Nice were sold to the BBC by Howard Marks when the landmark autobiography of perhaps the most sophisticated drug baron of all time topped the best seller lists in 1996. 15 years later, his vivid memoir was finally brought to the big screen by the iconic writer/director Bernard Rose (Candyman, Immortal Beloved) who faithfully captures the rambling, often comic, nature of the original book, aided by an outstanding performance from Rhys Ifans in the title role.

In researching this article I have found many prominent discrepancies between the reported facts, their fictionalised account in the original Marks book and the way in which they are presented by Rose in his screenplay. This opaque concept of reality has helped to give “Mr. Nice” his legendary outlaw status with comparisons drawn to Robin Hood and Butch Cassidy to name but two. Whilst this lack of absolute veracity might irritate some, to my mind it only serves to heighten the movie as a work of art in its own right.

In trying to echo the essence of an autobiography, Bernard Rose elected to take on most of the important technical roles behind the camera, not content with writing the script and directing the performances. He is also the cinematographer (operating a handheld 35mm camera to capture the requisite period look) as well as being the film’s editor. This singular vision provides a necessary counterpoint to the force of nature, that is Rhys Ifans which dominates almost every scene in the movie.

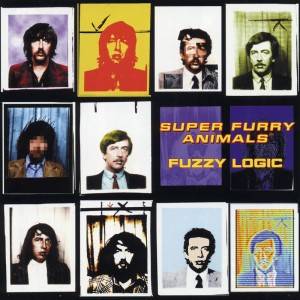

Ifans actually got to know Marks back in the day when he was singing with the fledgling Welsh psychedelic rock combo Super Furry Animals. Prior to the huge success of the book, the two became firm friends and a deal was struck that Rhys should play Howard if a film was ever made of his life. This long-standing amicable association provides the movie with a heart that would have most likely been missing with anyone else in the lead role. Ifan’s admiration for Marks is demonstrable, as is his compassion, particularly in the Terre Haute Penitentiary scenes.

The film opens from behind theatrical curtains with Howard Marks addressing a favourable crowd during one of his live shows. After the book’s success, he became a popular speaker on the raconteur circuit. It then flashes back to his early life in a small Welsh coal-mining village near Bridgend. The black and white film stock shrinks to a 4:3 ratio, giving the feeling of a kitchen sink drama of the period. The young Howard is also played by Rhys Ifans; a surreal device recollecting the televised plays of Dennis Potter.

Marks was the first of his family to attend university after earning a scholarship to study at Balliol College, Oxford, in the mid-1960s. Like many of his generation during his undergraduate years, he was exposed to a variety of recreational drugs, including LSD, but his drug of choice was cannabis, in particular hashish, as he takes his first toke the scope of the picture widens and dramatically shifts from monochrome to vivid colour, reminiscent of Dorothy’s entrance into Oz.

After Howard graduates from Oxford with a degree in Nuclear Physics, he heads back to Wales, gets married and starts a family. This is the version of events unique to Rose’s film, as this is not how Marks recalls it in his book nor is it true to documented accounts them but it makes perfect dramatic sense. He takes a steady teaching job to make ends meet and, for a while, leads a sober yet boring existence, until he attends a party thrown by his old college chum Graham (Jack Huston), who seems to be doing incredibly well for himself by selling hash. Howard is readily seduced back into the hippy culture when he meets and shares a joint with Judy (Chloë Sevigny), embarking on a long love affair with her and the weed.

When Graham is arrested while attempting to smuggle a large haul out of Germany, Howard agrees to courier the remaining stash back to the UK, where he is quickly baptised into the machinations of big-time drug dealing, turning a quick profit and agreeing to collect further shipments from the Pakistani supplier, Saleem Malik (Omid Djalili). This whirlwind period in Howard’s life brings him into contact with the colourful character of Jim McCann, the Irish freedom fighter allegedly kicked out of the IRA for drug trafficking, played full tilt by David Thewlis. Marks engages McCann’s Provo contacts at Shannon Airport to covertly import drugs from the European mainland.

In a surreal twist straight out of the pages of Ian Fleming or John le Carré, Howard is approached by another old chum from Baillol, Hamilton “Mac” McMillan, played by the wonderful Christian McKay (Me and Orson Welles), who now works for MI6 and wishes to recruit Marks as his eyes and ears in various cases relating to narcotics or terrorism in return for a level of protection from the law.

Between the late 70s and early 80s, Howard Marks amassed a complex network of connections controlling, at one point 10% of the global hashish market, and by the mid-80s he had 43 aliases, 89 phone lines, and 25 companies trading throughout the world. True to the book, the film tries to suggest that his fateful decision to move into the American market was his ultimate undoing and that Judy, who by this time he had 3 children with, tried to discourage the US expansion and pull Howard back to reality and the commitment of family life, but the temptation to make even greater piles of cash proved too much.

Bernard Rose employs a clever stylistic device to convey the 25-year time period covered in the course of the movie. He takes actual filmed stock footage backgrounds and then digitally superimposes Marks over the top, matching the grain, whilst the effect is an obvious artifice dismissed by some critics as simply amateurish and cheap it actually serves as a striking visual quirk that reflects Howard’s constant state of expanded consciousness. It also reminds me of the back projection shots favoured by Alfred Hitchcock in his golden Hollywood period, notably Marnie in 1964.

The original soundtrack by minimalist composer Philip Glass amounts to nothing more than incidental mood music echoing the sort of thing he did for the Errol Morris documentaries of the 80s starting with The Thin Blue Line. Nevertheless, it does help to bring about a sense of cohesion to the piece. For this level of attentive detail Rose should be commended. He has managed to make a visually unique movie and a wonderful star vehicle for Rhys Ifans out of a stoned shaggy dog story that will help maintain Howard Marks’ mythic stature as he continues his vigorous campaign for the legalisation of recreational drugs.