Inland Empire

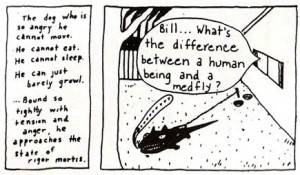

I was going to get around to reviewing Inland Empire on Blu-ray at some point but have been inspired to do so with a little more urgency by some surprisingly disparaging comments about it at, of all places, the Twin Peaks Gazette an online community dedicated to the seminal TV show and David Lynch’s oeuvre moreover. The general opinion is that this is a dog’s dinner of a film and that it has single-handedly killed his cinematic career.

I couldn’t disagree with these sentiments more vehemently, in my opinion it could very well be the crowning glory to a body work of great distinction. I admit it was never going to be to everybody’s taste, even those who have championed his more commercial efforts might well struggle with its epic running time and the fact it isn’t shot on celluloid but retrograde digital video cameras, operated entirely by Lynch himself. The film is both a showcase for the acting talents of long-standing muse Laura Dern and her intense, multifaceted performance eats up the screen, as well as a serious attempt to push the envelope of the cinematic medium as art.

The film’s detractors argue that it has no coherent plot and that the characters aren’t defined well enough to want to spend so much time with them. However, Dern’s stand out performance as Nikki Grace, a Hollywood starlet about to take on the female lead in drama steeped in adultery and murder only to find that it isn’t an original script, as she first thought, but a remake of an abandoned Polish movie that was believed to be ‘cursed’ according to the new film’s director, played with twinkling comic subtlety by Jeremy Irons. The former movie’s romantic leads died in mysterious circumstances and it would appear that the folk tale on which the plot is derived also has a horrifying history; benefitting from a masterfully dark central performance from the marvelous Peter J. Lucas.

The director urges Nikki and her leading man, Devon (a welcome return of Mulholland Drive’s Justin Theroux) not to panic as they will be perfectly safe; but as they rehearse the scenes the lines between the film’s story, the folk lore and the fate of the original couple transgress their own reality. Whilst this is familiar Lynch terrain it is in no way predictable, quite the opposite. The menacing mood and exceedingly surreal imagery, most notably a corny sitcom starring actors with rabbit heads complete with canned laughter, is intercut adding to the mounting disquiet and tension as Nikki is drawn deeper into the mystery.

I agree that there are elements of commonality between Inland Empire and Lynch’s previous film Mulholland Drive but no more than there were with its own predecessor Lost Highway, which was equally criticised when it first came out for being too dark and confusing, yet is now widely acclaimed as a Lynch classic. This is where the ‘art’ world vastly differs to the world of cinema where audiences expect a director’s new movie to be entirely different from their last. However, with both painting and music it is quite common for an artist or composer to do ‘variations on a theme’ throughout their careers.

Whilst I recognise that Inland Empire is the least accessible film David Lynch has made to date I think it is all the better for that and emerges as a true ‘work of art’. This is the type of expression we should expect from an artist who has been freed from the confines of budget, time and the interference of studio executives by embracing the digital medium. To try and compare Inland Empire even to Mulholland Drive, the first two thirds of which initially formed the pilot for TV series and therefore comes from a commercially aware sensibility, is like comparing apples and oranges. The only other film that comes close to it in Lynch’s canon would be Eraserhead and I’ve come to understand that when he said he was “done with film” he wasn’t simply meaning the medium in preference to digital; he was also referring to the limitations that commercial film distribution imposes on a creative artist and it’s a testament to the French, who have a true respect for ‘auteur’ cinema, that Canal+ continue to release David Lynch’s work.

It is probably wrong to even attempt to review Inland Empire, it is a film that should just be experienced with as little preconception as possible, perhaps it needs to be approached as one would a visit to an art gallery, wandering through it at a leisurely pace not quite expecting what will be around the corner or what surprise might be in the next room.